Oldest large lignite-based plant among the state’s cleanest

Jamey Backus, manager at the Leland Olds Station,

talks about the history of Basin Electric Power Cooperative

and the electrification of rural North Dakota.

The Leland Olds Station can trace its roots back to the early 1960s when rural America was starving for electricity. Available electricity from dams on the Missouri River had been swallowed up by the farmers who found that power made their farm chores – such as milking cows and irrigating crops – faster and easier.

In fact, the rural electric cooperatives adopted a mascot – Willie Wiredhand – a cartoon man with legs made out of an electric plug – and whose attributes included “showing up on time, working for pennies a day, and taking over the milking, grain handling, water pumping and other chores…and he didn’t talk back to the boss.”

To supplement the electricity generated by the dams, generation and transmission cooperatives – including Basin Electric Power Cooperative – were created to generate the same baseload electricity as dams, but from coal.

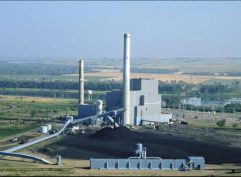

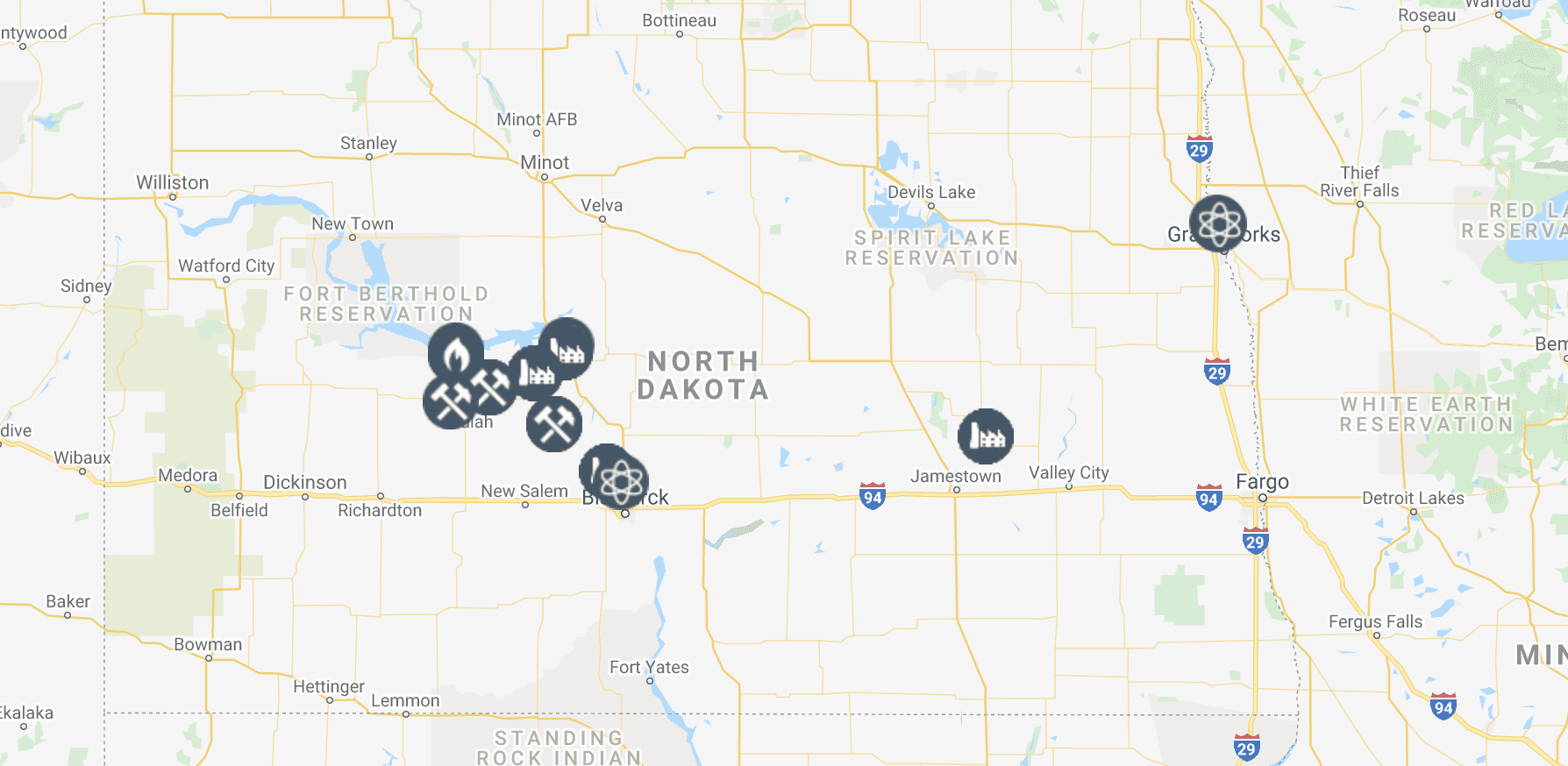

Basin Electric’s first lignite-based power plant was the Leland Olds Station built along the shores of the Missouri River near Stanton, North Dakota. Completed in 1966, the first unit of the plant generated 216 megawatts of electricity – about one-third the capacity of the massive Garrison Dam just up the river from Stanton. A second unit was added in 1971 with a capacity of 440 megawatts. Together, the Leland Olds Station has a capacity of 616 megawatts, which is more than the Garrison Dam’s output of 583 megawatts. One megawatt is enough power to serve about 800 customers.

Jamey Backus is the current manager of the station, which has added a number of different environmental control systems in the past 10 years to ensure the plant continues to operate within the boundaries of increasingly strict federal air quality regulations.

“The largest project has been the $410 million investment by Basin Electric to capture about 98 percent of the sulfur dioxide through the two limestone-based wet scrubbers,” Backus said. “The project started with engineering about 10 years ago. A number of components had to be built and added onto the existing power plants.”

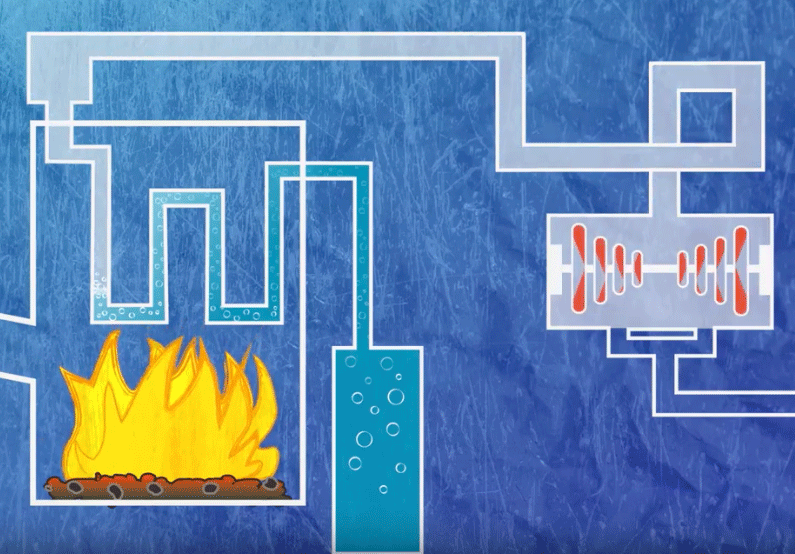

A slurry made of limestone is sprayed into the flue gas stream to capture the sulfur dioxide in the wet scrubbers. Since the limestone comes from out-of-state, the power plant had to build equipment to take deliveries of the limestone and store it onsite until it is used. A new chimney with individual fiberglass flues serving each unit also had to be built. Fiberglass flues are used due to the additional moisture and corrosive nature of the flue gas stream exhaust from a wet scrubber.

In addition to the wet scrubber for sulfur dioxide control other additional controls nitrous oxides, mercury and fly ash are also installed and operated at LOS. Electrostatic precipitators in combination with the wet scrubber remove more than 99 percent of the particulate created by burning lignite in the boilers.

Nitrous oxides are reduced through the use of layered NOx controls of over-fire air in combination with injection of urea in a selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR) system. Nitrogen is an inert ingredient found in lignite, and is the majority gas constituent in the air of which both are required for combustion. Good combustion controls attempt to limit the amount of thermal nitrogen oxide formation in the extreme heat located in the boilers. By using a combination of over-fire air, which allows the coal to be burned at different oxygen stages in the boiler, along with SNCR technology, the station is able to control NOx emissions.

Since April 2015, the Leland Olds Station has also significantly reduced its mercury emissions. The station was a primary test site a decade ago for research and development projects to control emissions of mercury from lignite-based power plants. Through the use of activated carbon, the station can now reduce its mercury emissions efficiently while continuing to produce electricity for Basin Electric’s customers.

The station buys about 3.3 million tons of lignite annually from The Coteau Properties Company’s Freedom Mine. The coal is shipped 25 miles by railroad from a tipple located at the Antelope Valley Station to the power plant.

“While we do receive our coal by rail, the Leland Olds Station is still considered a mine-mouth plant because the shipping charge is minimal,” Backus said. “Because of the inexpensive fuel, we are able to produce electricity at a very competitive price.”

He notes that with the proliferation of wind turbines in North Dakota and elsewhere, wholesale electricity prices are competitive and being a low-cost producer is important to the station and its 175 employees.

“We continue to be a baseload supplier of electricity,” he said. “We run at or near capacity most of the time. However, we might be asked to reduce our generation during the night or during the weekends, depending upon weather and other conditions.”

This year, the first unit of the Leland Olds Station turned 50, but with the recent pollution control upgrades, the power plant is ready to positioned to continue producing megawatts in an environmentally compliant manner for a long time to come.