Minnesota Legislative Session Ends In Special Session

For people who live in North Dakota, it can be very difficult to understand the legislative process in Minnesota. There are major differences between both the political makeup and the way that the legislature operates between the two states. For example, in North Dakota there are limits on the amount of bills that a legislator can introduce while every bill introduced receives a committee hearing and a floor vote. In Minnesota, there are no limits on the amount of bills introduced and there is no requirement that a bill receives a hearing or a vote.

While there are many other significant differences, North Dakota does not rely on omnibus budget bills filled with policy proposals as Minnesota does. This long-standing practice leads to a strong focus on political strategy for crafting the provisions in the competing versions of the omnibus bills in the House and the Senate to allow for ‘horse trading’ during the end of session negotiations. Those negotiations take place within the assigned conference committees between the House and Senate members and within the leadership meetings between the Senate Majority Leader, Speaker of the House and the Governor.

The process that customarily takes place is for the conference committees to hold public hearings in order to debate and make decisions upon the provisions that will be included in the final bill. This typically takes place over the span of a few weeks where the control of each hearing is decided in a revolving fashion where the committee gavel flips back and forth between the bodies. During this time, there are also private conversations between committee chairs, the legislators that are typically the most familiar with the detailed policy and sending provisions, to negotiate the differences between their respective bills.

Each of the ten budget bills have conference committees consisting of five appointed members of the House and five appointed members of the Senate. The members who worked on this session’s Jobs and Energy Omnibus Bill Conference Committee were Senator Eric Pratt (R-Prior Lake), Senator Dave Osmek (R-Mound), Senator Gary Dahms (R-Redwood Falls), Senator Karin Housley (R-Stillwater), Senator Erik Simonson (DFL-Duluth), Rep. Tim Mahoney (DFL-St. Paul), Rep. Jean Wagenius (DFL-Minneapolis), Rep. Zack Stephenson (DFL-Coon Rapids), Rep. Jamie Long (DFL-Minneapolis) and Rep. Hodan Hassan (DFL-Minneapolis).

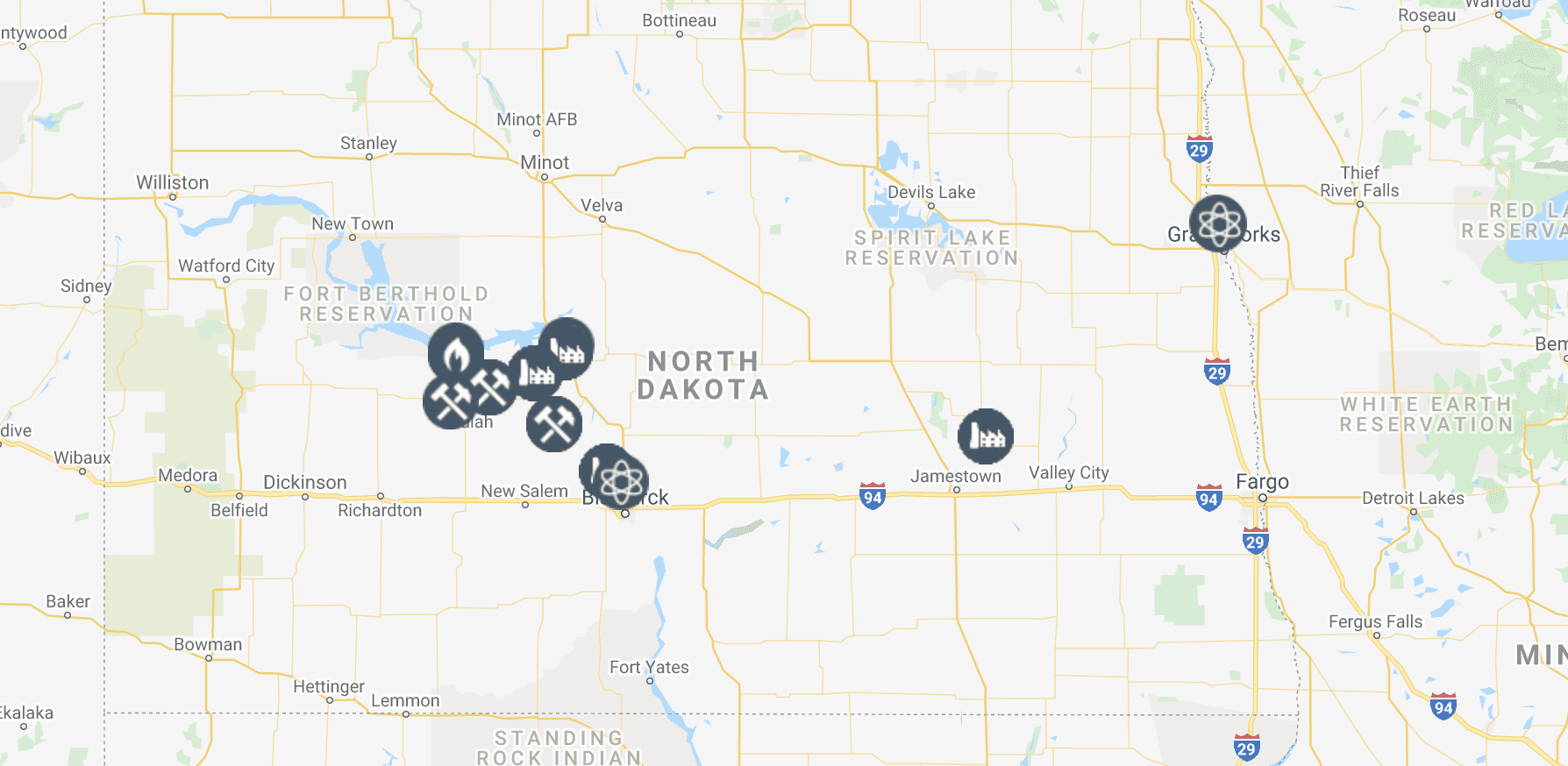

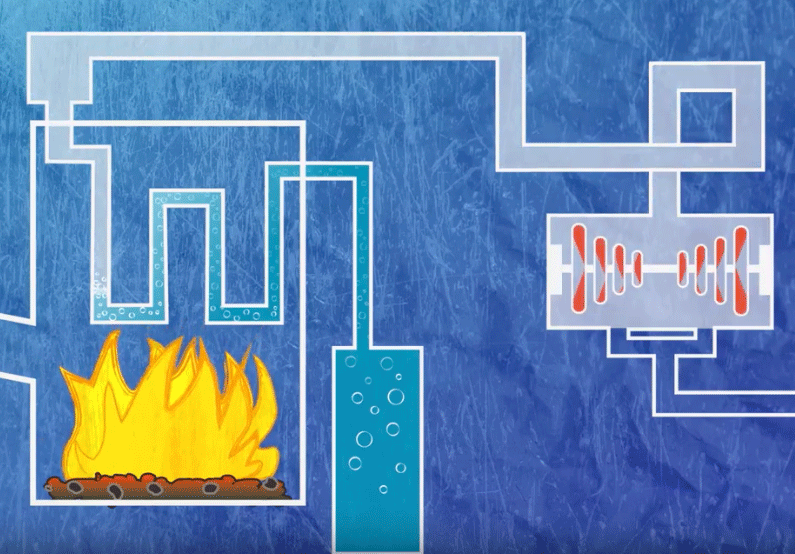

Going into conference, the two competing versions of the jobs and energy bill were drastically different in nearly all phases. Most notably, the House of Representatives passed two sweeping energy proposals (both strongly supported by Governor Walz) in the 100% carbon free by 2050 and the Clean Energy First Act, which that could cause great damage to North Dakota’s economy. The 100% carbon free by 2050 bill would require that all Minnesota-based utilities provide only renewable-based energy by that date. This mandate would make it illegal to be able to purchase lignite-produced energy from North Dakota power plants and mines ending the exportation of our homegrown lignite electricity to Minnesota. The Clean Energy First Act would mandate that whenever a utility proposes to replace or build a new power generation source – energy efficiency and renewable energy sources such as solar and wind be prioritized over fossil fuels. The caveat is that fossil fuels could only be used if necessary to ensure reliable, affordable electricity after a lengthy hearing process at the Public Utility Commission where a utility would have to prove that renewable-only generation could not be met at an acceptable price for ratepayers. In contrast, the Senate did not hold a hearing for the 100% carbon free by 2050 mandate but they did hold a hearing on a different version of a Clean Energy First Act, which included carbon capture as a clean energy source but did not include it in the omnibus bill.

The jobs and energy conference committee ended up holding a handful of hearings and each did so with different approaches to completing their work. For example, when the House held the gavel they brought in select testifiers to highlight the need to accept the House provisions to address climate concerns. Those hearings did not allow for public testimony that could provide another viewpoint to the testimony. When the Senate controlled the gavel, the committee did a walk-through of the provisions in the bill and made motions to adopt same and similar provisions that the House also carried into conference. Almost every hearing consisted of some very tense moments and it was clear to those skilled legislative observers that a deal was going to be hard to achieve since each side’s provisions were so far apart and not much progress was being made, for better or worse, in the hearing process.

In the final week of the regular session, the committee did not meet much as they were at a stalemate waiting for the leadership negotiations to agree on a budget target. This was the same set of circumstances that most, if not all committees, were under. With about 28 hours to go before the constitutional deadline, the leaders held a press conference where they announced a global deal that set aside most policy provisions and set hard financial spending targets in each committee jurisdiction.

Once the leadership press conference ended, committee chairs met in private to try to reach deals on the remaining issues in the bill. There have been some press reports that sought to explain the partisan differences over energy policy that loomed large over those conversations.

MinnPost Article: “Why the Legislatures Energy & Climate Budget Does a Whole Lot of Nothing”